After decades of counting calories and munching on fat-free snacks, new literature dropped a pretty big bombshell: we’ve been approaching our diet all wrong.

Ultra-Processed People broke the story wide open. Its author, Chris van Tulleken, has continued to spread the word about ultra-processed foods (UPF) by creating a documentary and speaking on several big-name podcasts.

His efforts are paying off, with Google searches for “ultra-processed food” peaking in December 2024, and his book being one of Amazon’s 2024 bestsellers. It seems people are digesting the idea - even if it’s a hard one to stomach.

What are ultra-processed foods, anyway?

The technical classification of ultra-processed foods comes from a Brazilian professor, Carlos Monteiro, but it’s now broadly understood by Chris Van Tulleken’s definition:

“If it’s wrapped in plastic, or it’s got something in it you don’t find in the domestic kitchen, it’s ultra-processed food”.

Through this lens, food labels like “vitamin-enriched” or “fortified” come under the spotlight, as they suggest that some of the nutrients lost during processing have been re-added.

Turning decades of dietary and nutrition advice on its head, this fairly new way of thinking suggests that it’s not the fat or sugar content in our food that’s causing health problems, but how processed it is. And we’re at an interesting point in its journey: this growing body of research has broken out of the lab and into culture.

Who’s most concerned about ultra-processed food?

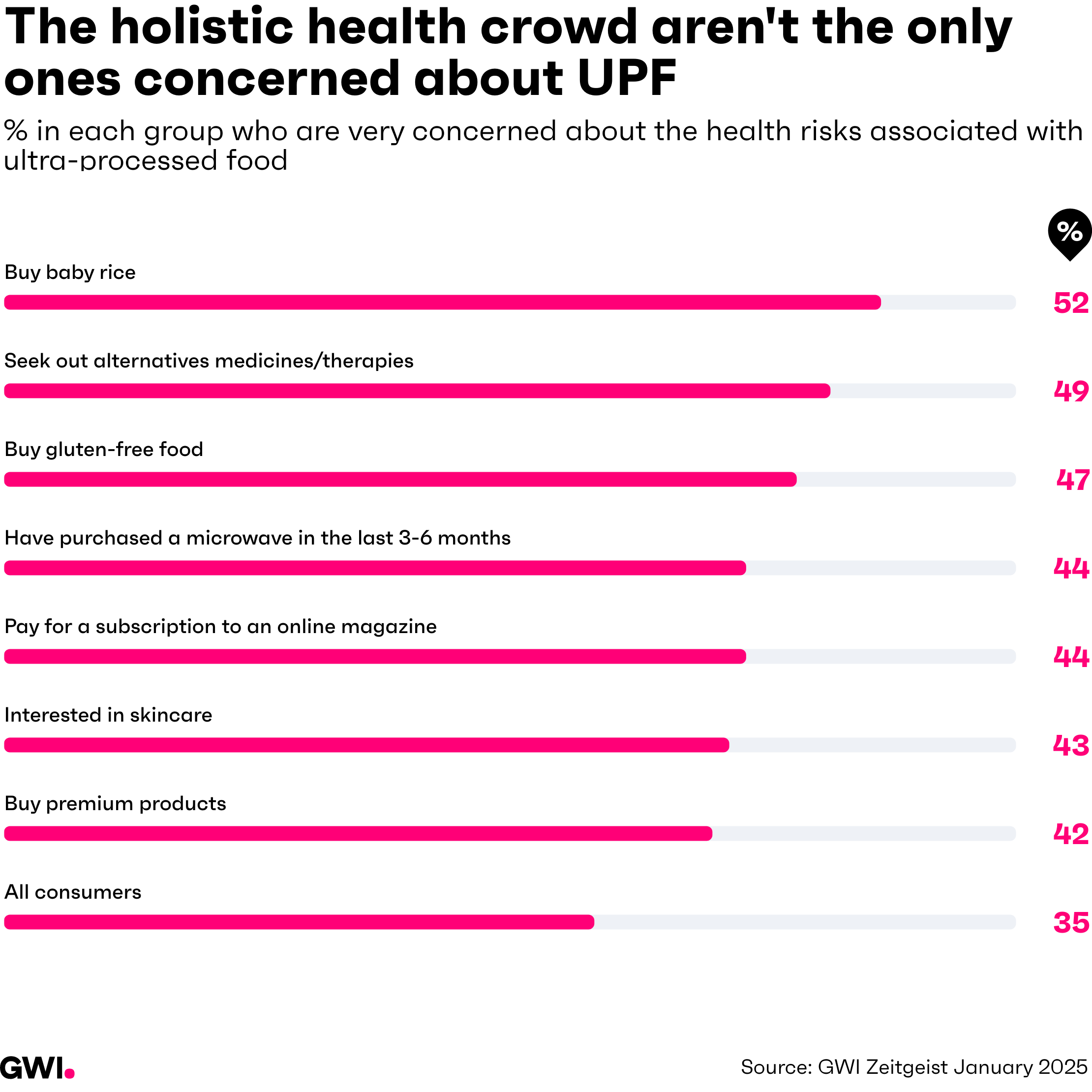

77% of consumers are concerned about the health risks associated with UPF, with 35% saying they’re very concerned. This is higher than the share of consumers who agree that social media is harmful (66%) or very harmful (31%) for children. It’s rare for concern or agreement to be so universal among consumers.

Still, it helps to zero in a bit and put the groups most scared of UPF under the microscope.

Some are what you’d expect - older women interested in skincare, nature, and alternative therapies. Often chasing purity in mind, body, and soul, they’re already tuned into wellness messaging. They’re the kinds of people who might read lifestyle magazines or follow relatable celebrities posting about UPF. Emma Thompson has openly promoted the book Spoon-fed, which encourages us to ignore a lot of what’s been written about food; while others like Caroline Lucas and Joanna Lumley have spoken out against industrial farming methods.

Often with more time and resources to research food trends, high earners are also more concerned about UPF, which means premium brands have a stronger incentive to make relevant tweaks to their marketing and products.

Other audiences catch you off guard, like those who buy baby food, gluten-free items, or have purchased a microwave recently. New parents are generally more concerned about societal issues, so the UPF conversation has a stronger chance of resonating with them. If you’re already scanning labels for gluten, you’re probably more likely to notice hard-to-pronounce ingredients. And in the case of microwave buyers, there could be some kind of “ready meal regret” going on, having seen the impact convenience food has had on their lives in a short space of time.

This shows that the UPF debate doesn’t exist in a bubble - it’s turning heads in all sorts of places, for all sorts of reasons.

Why is this happening now?

A fair few brands have previously created campaigns that highlight their lack of additives or preservatives, and there are signs that the time is ripe for UPF-related discussion, and that this discourse is part of something bigger.

There’s been an ongoing rise in people buying probiotics or taking digestive supplements. And with conditions like IBS on the rise, gut health has been getting more attention. There’s probably a lot of people looking for answers or solutions, which they can find in the UPF narrative.

What’s more, drops in people buying vegan and traditional diet products can be linked back to the fact that many are ultra-processed, something that’s been put in the spotlight on various occasions. A Super Bowl ad from 2020, kids at a spelling bee trying and failing to spell a plant-based product's additive, is a prime example.

Can people identify ultra-processed foods?

Right now, people feel quite UPF-savvy - in fact, 62% say they’re somewhat or very confident that they understand the term. And they’re not bad at spotting it in the real-world either. The majority can correctly identify that instant noodles, ready meals, and sausages/burgers are ultra-processed.

|

Food item |

% who believe it's ultra-processed |

Ultra-processed or not? |

|

Instant soup/noodles |

64 |

Yes |

|

Ready meals |

62 |

Yes |

|

Sausages/burgers |

56 |

Yes |

|

Breakfast cereal |

39 |

Yes |

|

Canned vegetables |

28 |

No |

|

Chocolate |

23 |

Yes |

|

Infant formula |

17 |

Yes |

|

Smoked meat/fish |

16 |

No |

|

Cheese |

15 |

No |

|

Table salt |

8 |

No |

|

Coffee |

6 |

No |

A few things trip us up though. Cereal boxes have attracted criticism from some quarters, as they're believed to hide behind misleading health claims, fun cartoon mascots, or colorful packaging. But not many people view them as UPF.

Then there are times when consumers mistake merely processed foods for ultra-processed foods. According to the NOVA classification system, processed foods simply have one or two ingredients added for longer shelf life or better flavor. Canned vegetables fall into this category - some wrongly assume they’re UPF, possibly because we hold them up against fresh vegetables. It’s a shame too, as they’re a cost-effective way for many people to meet their fiber requirements. Tinned goods manufacturers could address this mix-up and work to flip the script.

One last thing to draw your attention to is infant formula, which just 17% recognize is UPF. It also raises an important caveat when discussing UPF: it can be life-saving. Some mothers can’t breastfeed, afford organic products, or find time to make meals from scratch. Education pieces that make people aware that infant formula is UPF, but ground that message in context, could help them make informed decisions. And this is arguably a key point to make in any ultra-processed food conversation: how much of it can we realistically cut out, and are there occasions where it might be necessary - or even beneficial?

What should food brands be asking themselves?

There are several takeaways for food brands to consider when reviewing their product development or marketing strategies.

- The UPF information is out there and we can’t put it back in its box. It will impact the food industry, we’re just not sure by how much.

- The ingredients list is becoming an important part of packaging. Products that put it front-and-center, with shorter lists, will probably be seen as more credible.

- High-protein products, which are trending big time, could lose steam like vegan or diet items if shoppers continue to draw attention to the additives some contain. Businesses selling them should keep this in mind.

- There’s room for more food subscriptions that satisfy people’s craving for home-cooked meals and convenience.

- New regulation is set to raise the stakes. In 2014, Brazil made a rule to put small print front-and-center, essentially what M&S is doing on a national scale. The government also insisted manufacturers put warnings on food, as other markets do for alcohol or tobacco. Not only did snack purchases start to drop, but Brazil is now the world leader for buying health foods.

- Other markets are likely to follow suit, with the new US health secretary raising concerns about UPF and poor nutrition.

Generally speaking, shifting consumer preferences combined with new legislation is a recipe for meaningful change, and businesses that cater to fresh priorities are likely to stay on the menu.

.webp?width=495&height=317&name=pink_thumb_graphs%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=495&height=317&name=pink_thumb_letter%20(2).webp)